by an old mooring

a few steps

carved out of rock

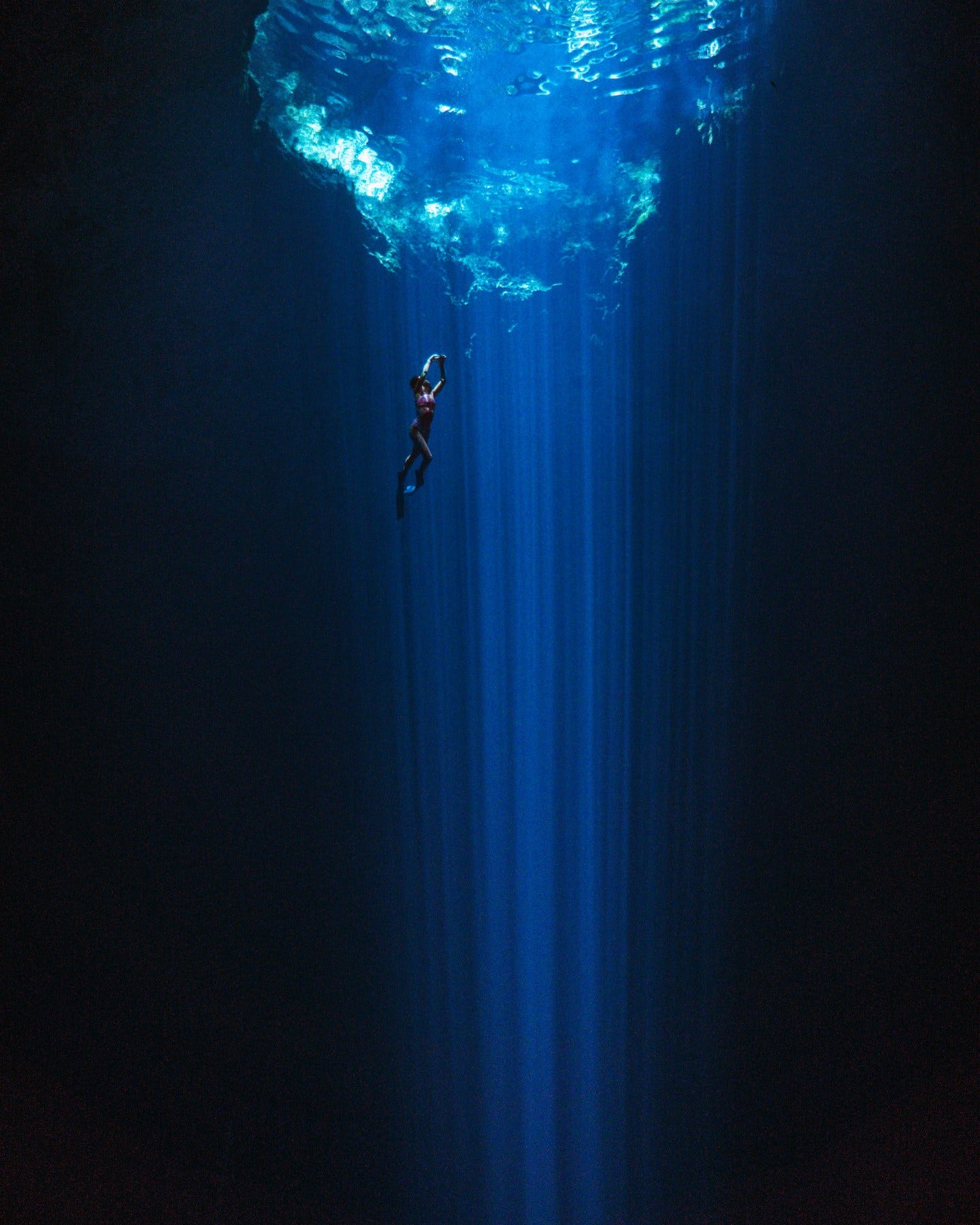

go down to wateras if you might

step down into the sea

into another knowledge

wild and cold— Thomas A. Clarke, The Hundred Thousand Places

I remember the last moments of my childhood.

I was young, and my family had a holiday house by a lake in the mountains. One winter night, as I was walking home along a path by the shore, I came across an old jetty - half collapsed, but strong enough to bear my weight as I climbed to the end, over the dark and still water.

Somehow I knew that this moment was a test. It was a test that no one else would witness or understand. But I could not deny or ignore the call to get into the water and dive down beneath the obsidian ripples.

Looking at the black surface, my heart was up. I knew that it would be freezing. People died in this lake - one neighbor had had a heart attack. It was deep and unforgiving.

I had had a taste of that fear before: one morning I had dared myself to swim around a bouy a few hundred meters out, without realising how taxing the swim would be in freshwater. Moving over the depths on the way back, feeling my breath go, I knew I had no choice but to keep swimming.

But this night, my task was different. It was no feat of endurance, but a simple act of daring. Alone, without anyone knowing where I was or what I was attempting, I had to slip down into the dark. There would be no rescue.

I stripped and jumped. The cold slammed into me, spiking my heart rate, causing my body to immediately demand oxygen. I surfaced and breathed until I was shivering but basically calm and had a measure of control. Then I dived.

At the bottom, perhaps ten meters down, I stopped. Everything was still. I ceased moving, releasing all tension in my limbs, floating in place. The only sounds were heavy, deep, and slow - the water itself, gently pressing against my skull. It was utterly dark.

Raw adrenaline gave way to a steady energy. It hummed in my chest, intense but controlled.

I knew I was in a space where death was possible. I could die here. I was not unsafe - there was no immanent threat - but I was in-safe. I lacked all protection and supervision, totally alone with the forces of the environment I inhabited.

In that moment, responsible for my own life, I knew that I had crossed a threshold. Intentionally risking my life in order to meet the demands of existence was not the activity of a child. Perhaps I was not yet a man, but my childhood was over.

I kicked back towards the surface.

I reflect on those moments more than any other from that period of my life. I hope that as my son grows older, I will have the strength to allow him to risk his own life, even in the pursuit of ideals I don’t fully understand.

Heidegger believed that it was only in the existential Angst brought about by a confrontation with Nothingness that man can enter into an authentic mode of Being, and that only an acceptance of death - the coming of the Nothingness - could bring this anxiety to the requisite heights.

In Heidegger’s magnum opus, Being and Time, existence is a miracle that cannot be appreciated unless one is willing to stretch one’s thoughts beyond the limits of what exists, to consider that which lies beyond Being. One must focus one’s mind on that inconceivable void without which the concept of Being would be meaningless: the Nothing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Becoming Noble to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.