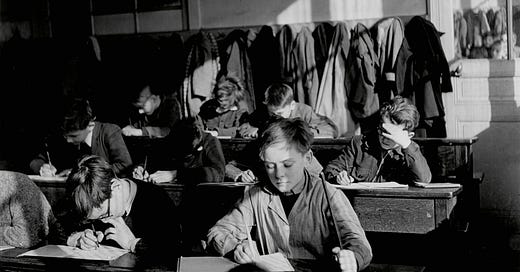

Meritocratic education ruins children

Meritocracy II: The credentialism & technocratic rat race

In Meritocracy is not a good thing, I began a critical examination of the premises inherent in our modern system of ‘meritocracy’.

Meritocracy is a concept which initially appears unassailable; should not the person who merits the reward receive it? And yet, as my friend

recently pointed out in conversation with , this naive definition is tautological …Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Becoming Noble to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.