It's embarrassing to be a stay-at-home mom

Addressing the actual cause of collapsing fertility: status

Fertility is collapsing worldwide. We lack a coherent theory for why this is happening. As we shall see, the conventional explanations - changes in economics, housing, religiosity, contraception, and childcare - don’t fit the macro data and cannot be the fundamental drivers of the trend. Each of these factors may play an important role in certain circumstances, but none is the ultimate cause of the broader collapse. None has sufficient predictive power upon which to build effective policy. Once I have demonstrated this, I will propose an alternative theory, and use this theory to suggest policy which will significantly increase birthrates.

Economic interventions fail. Hungary spends an incredible 5% of its GDP on its fertility drive through the provision of financial incentives: significant loans, tax breaks, subsidized fertility treatments. Its dire situation has moderately improved, but overall fertility remains far below replacement levels, with a rate of 1.59 births per woman (fewer than the US at 1.66). A society needs a birthrate of 2.1 to sustain itself.

The Nordic nations offer further economic and lifestyle benefits to parents through exceptional state-backed parental leave and childcare policies, with the World Economic Forum describing them as “the best places to have children” in the world. In some, women can take more than a year’s parental leave, challenging the argument that the need to work is blocking women from having children. These countries also have some of the lowest fertility rates in the world, and they continue to fall.

Religiosity alone does not appear to have the answer. Even if you isolate the most religious population (weekly church attenders) within the most religious of the major Western countries (the USA), you find barely breakeven fertility rates, with churches unable to sustain themselves due to defections to secularism. The three most religious European countries (Romania, Moldova, Greece) all have negative population growth, with Greece’s fertility rate a catastrophically low 1.39 births per woman. Iran - which can reasonably be described as an actual theocracy - has an unsustainably low TFR (1.69).

The last decade has seen a substantial increase in the share of millennials who own homes (by 2022, more than 50% of US millennials were homeowners), but childlessness in the same cohort has continued apace.

The collapse in fertility rates in the Western world long precedes the advent of oral contraceptive pills, as well as endocrine disruptors and other relevant chemical agents which might be interfering with fertility health.

I could go on, but you get the picture: conventional explanations don’t work in any kind of consistent and predictable fashion, including the (seemingly credible) explanations most commonly given by the actual cohorts which have failed to have children. Failing to accept this leads to disaster, like South Korea spending hundreds of billions on economic incentives to have children, only for their birthrate to drop yet faster.

We are thus presented with an apparent paradox: a stable trend which continues to unfold across the West, in country after country, generation after generation, without an obvious causal logic. How is this to be explained?

I propose that there is, in fact, an under-appreciated fundamental cause of these trends, which manifests in the form of different proximate causes (real and imagined) across different geographies and times.

This fundamental cause is status.

Specifically, I contend that the basic epistemological assumptions which underpin modern civilization result in the net status outcome of having a child being lower than the status outcomes of various competing undertakings, and that this results in a population-wide hyper-sensitivity to any and all adverse factors which make having children more difficult, whatever these may be in a given society.

In such a paradigm, if a tradeoff is to be made between having children and another activity which results in higher status conferral (an example would be ‘pursuing a successful career’ for women) then having children will be deprioritized. Because having and raising children is inherently difficult, expensive, and time-consuming, these tradeoffs are common, and so the act of having children is commonly and widely suppressed.

Here it is worth defining terms. What is status?

Status, or ‘social status’, is a key field within sociology. The term denotes a universal set of human instincts and behaviors. Status describes the perceived standing of the individual within the group. It denotes their social value and their place within the formal and informal hierarchies which comprise a society. It finds expression in the behaviors of deference, access, inclusion, approval, acclaim, respect, and honor (and indeed in their opposites - rejection, ostracization, humiliation, and so forth).

Higher status individuals are trusted with influential decisions (power), participation in productive ventures (resources), social support (health), and access to desirable mates (reproduction).

Gaining status is a motivation for each individual to productively participate in society. Status is gained and maintained through approved behaviors (achievement, etiquette, defending the group) and through the possession of recognized ‘status symbols’ (titles, wealth, important physical assets).

For the group, status has utility when coordinating social actions: it serves as a proxy measure for attributes like probable competence, leadership capacity, and virtue.

As Will Storr describes in ‘The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It’:

We play for status, if only subtly, with every social interaction, every contribution we make to work, love or family life and every internet post. We play with how we dress, how we speak and what we believe. We play with our lives – with the story we tell of our past and our dreams of the future. Our waking existence is accompanied by its racing commentary of emotions: we can feel horrors when we slip, even by a fraction, and taste ecstasy when we soar.

As an explanatory factor, status has the advantage of being a relative - as opposed to absolute - attribute. Ascribing primary explanatory status to any absolute factor is challenging because almost all material factors have improved over the last two centuries, while fertility has dropped. It is difficult to make a straightforward economic argument that millennials can’t have children for financial security reasons when their ancestors had a higher fertility rate while living in far greater poverty (and had such medical and food insecurity that they would have expected several of their children to die in childhood).

Status is also of existential importance to individuals. This is necessary for our inquiry because we are seeking a behavioral determinant which is powerful enough to influence fundamental human decisions like whether or not to reproduce. Sudden downwards social mobility is a well-established cause of suicide, and this effect is observable even amongst those who have experienced no change in their own material circumstances but have been ‘left behind’ as their peers make gains.1 Status is very important to us indeed.

If the pursuit of status was indeed the primary causal factor in suppressing fertility rates, we would expect to see:

Interventions which increase the status of parents to increase fertility;

Communities in which parents are higher status to have higher fertility;

High-status individuals who become parents causing others to follow suit;

‘Social strivers’ to forgo children for higher status objectives;

‘Status secure’ people (established elites) to have higher fertility;

Groups with unusual status systems to have unusual fertility patterns.

Unlike our earlier attempts to map global fertility data onto conventional explanations (the economy, religion, and so forth), we will see that the above list can be demonstrated to closely align with current realities, across countries and across time, even as proximate causes change. And, unlike those based on conventional explanations, interventions which center on status can quickly push a group’s birthrate far beyond replacement levels. (This is to be expected - status can offer a positive motivation for having children, as opposed to economic interventions, which can realistically only mitigate the burden of having children).

Let us turn to the first of the small number of European and Asian countries which defy wider fertility trends. This is the country of Georgia, which sits at the intersection of the two continents, with a population of about four million.

In the mid 2000s, Georgia spiked its birth rate, which went from ~50,000 to ~64,000 over the course of two years - a 28% increase, which it sustained for many years. The country went from poor to replacement-level fertility, and it did so without spending more money or changing policy. What caused this?

The evidence points to an unusual factor: a prominent Patriarch of the popular Georgian Orthodox Church, Ilia II, announced that he would personally baptize and become godfather to all third children onwards. Births of third children boomed (so much so, in fact, that it eclipsed continuing declines in first and second children).

This has widely been understood as a religious phenomenon, but I propose that it is better understood as a status phenomenon. Becoming associated with a celebrity figure who becomes, in some sense, an intimate part of your family is an event which is primarily attractive because of our desire to be elevated in status.

There is considerable evidence that people emulate celebrity fertility trends more generally. Individuals with high-status who become parents cause others to follow suit (which is why Taylor Swift’s pregnancy status is so carefully followed). The prevalence of out-of-wedlock births among celebrities likely played a key role in normalizing the practice for the general population, which followed their lead.2 This is to be expected: it has long been known that fertility is subject to strong mimetic effects, and that - even controlling for other factors - an individual’s chances of having a child significantly increase after a close friend has one.3

The implications of these dynamics are likely also true in the negative: celebrities and friends prioritizing other pursuits over having children probably suppresses fertility. Status is to be found elsewhere.

This takes us to the next test for our status thesis: do social strivers have fewer children? (I use ‘social strivers’ as a crude term for upwardly mobile but resource-constrained middle classes. Both the permanent underclass and the established elites have different fertility behaviors, as we shall see).

First, let’s note that goods which are essential for social status are in constant demand, even if they become very expensive. College attendance, for example, is near all-time-highs, even while most Americans now say that the education and career gains are not worth the extraordinary costs. This is because college attendance is understood as a necessary gateway into polite (high-status) society, whatever the cost may be.

Demand for children is not this robust. We are increasingly seeing that resource-limited parents would rather have a smaller number of children who secure places at elite universities than a larger number of children who do not. This is because - whether the parents admit it to themselves or not - the status reward of ‘having a child at an elite university’ is far higher than merely ‘having children’ (which presents a negligible status reward in our current society, and can be actively embarrassing if they ‘underperform’).

This is true for the Western middle classes, but it is even more true for the Asian middle classes, which - due to structural factors - are subject to more extreme variations of the same pressures and whose fertility has further fallen accordingly.

Take the canonical example of collapsing fertility: South Korea (with a catastrophic TFR of 0.68). The country’s birthrate continues to plummet even as the government spends hundreds of billions to provide economic incentives for parents.

Thanks to the Korean formalized systems of etiquette, language, and titles, social hierarchies are clear, explicit, and prominent. Because each person’s social status is unambiguous, individuals are incentivized to take whatever measures are necessary to ensure that their rank within the system is maximized. This process finds particular expression within the structure of the Korean economy, in which the only high-status employers are the small number of industrial mega-conglomerates like Samsung (the so-called ‘chaebols’). Gaining entry to and rank within these corporations has become of existential importance.

Fertility expert Malcolm Collins, who worked in the country, recently offered some fascinating reflections on Korean social pressures:

To understand how much the chaebol system matters in Korea: you are not a person of equal status to other people if you don't work at one of the chaebols. The chaebols are extremely important to your social status within Korea… your life is spent to try to get that perfect test score so you can get into the perfect chaebol.

Competition is fierce, and hinges on each individual’s performance in the national exam which determines university places. This exam is so important that they ground all planes and clear traffic on the one day each year it occurs.

Each child must receive exceptional training to perform at this exam. This means that the small number of couples who choose to compromise their own status performance to have children must pay for extended, expensive tutoring, and this in turn precludes almost all couples from having large families.

If striving for status is causing people to forgo having children, we would conversely expect to see those people who have less reason to strive to have more children. To denote this new group, I will use the term ‘status secure’. In contrast to the upwardly mobile middle-classes (‘strivers’), this group is largely comprised of stable elites, who are remarkable for their existing wealth and possession of status symbols.

In the absence of a true aristocracy, our best candidate cohort for the ‘status secure’ is probably the ultra-rich (here defined as families with an annual income over $1m). This is also the only economic class in America with above replacement-level birthrates (about 2.15).

When I began studying this, I thought that I might have to perform careful analysis to disaggregate the status elements at play from the purely economic, since it might be that the ultra-rich can simply afford children while others cannot. It turns out that this isn’t really necessary, since the data speaks for itself. The next income bracket down - those families earning between $500k & $1m a year - have significantly below replacement-level fertility (about 1.85). I don’t think it’s reasonable to argue that these families ‘cannot afford’ more than one child.

My contention is that for the ultra-rich, the status game takes on different contours. The most salient feature of this difference is that at a certain level of wealth, the highest status activity for a wife is no longer to ‘have a career’; it is to move in the right circles, to attend the right events, to support the right charities, to have the most beautiful houses, and so forth. Importantly, while the striver choice of having a career forces a tradeoff with having children, this elite strategy does not. In such circumstances, well-bred children might actually be a unique status asset.

Our final test for our status thesis is whether populations with unique or isolated status systems have unusual fertility patterns. Here I will use ‘cultural difference and isolation’ as a rough proxy for groups having different status signaling systems, but later I will return to this subject to provide a more careful breakdown of the status mechanics at play.

As Adam van Buskirk describes in Industrial Civilization Needs a Biological Future:

Ultra-orthodox Jews have birthrates of up to 7 children per woman, even in the middle of major Western cities. The Amish also show the dramatic effects of a pro-natal subculture. While rural women, in general, have a TFR of around 2.08, Pennsylvania Dutch-speaking women without a phone have an incredible rate of 7.14. This is a fertility rate higher than Niger while living in the United States.

The ‘why’ and the ‘how’ of the incredible fertility levels of these particular communities bear more examination, and to this I will shortly return. It is not merely that they are ‘very religious’. There is something particular about their cultural isolation and the structure of their social constitution which facilitates birthrates that other religious groups could only dream of. Spoiler: it concerns unique social mechanisms available for elevating the status of parents. We’ll need to understand what the features of their status systems are - more on this shortly.

At the national level, Mongolia supports the isolation thesis. One of the only European or Asian countries with a high birthrate (2.84), it has unusual demographic features for a large country. A very small percentage of the population is fluent in English (due in part to Soviet suppression). They’re ethnically and linguistically homogenous, geographically isolated, non-Christian, and have their own alphabet. In other words, our cultural mechanics have less purchase there than in almost all other Northern Hemisphere countries.

We start to see a trend emerge: the more isolated a population is from liberal modernity, the higher their fertility. And, our theory goes, this is due to the fact that in a modern liberal paradigm, having children provides a lower status payoff than competing pursuits.

But why should this be? What has changed over the last few hundred years? Why has having children become relatively low status, and how has this view spread around the world? What do we actually mean by ‘liberal modernity’?

Earlier I blamed the “basic epistemological assumptions which underpin modern civilization”. It’s time I spelled these out.

A useful model we can take from the literature is to classify the sources of status into three types: dominance, virtue, and success. Will Storr describes:

In dominance games, status is coerced by force or fear. In virtue games, status is awarded to players who are conspicuously dutiful, obedient and moralistic. In success games, status is awarded for the achievement of closely specified outcomes, beyond simply winning, that require skill, talent or knowledge.4

In the pre-Enlightenment period, a woman’s status was defined by her birth (class), maintained by her virtue (virginity, piety, motherhood), and modified substantially by her husband’s status. The primary sources of her status were therefore upheld by the Church (which held a role of social dominance incomparable to today) and her family (embedded within a formalized class structure).

In other words, the pre-Enlightenment woman derived her status from virtue and dominance games. These virtue strategies did not tradeoff with fertility, and likely supported it, with the Church teaching ‘conjugal duty’ and families demanding heirs.

The Enlightenment brought with it not just intellectual, economic, and scientific revolutions - it drove a status revolution. It challenged the dominance of the Church and aristocracy through the elevation of the ideals of equality, freethinking, and meritocracy.

In turn, this emphasis on the moral primacy of meritocracy changed the primary status game from dominance and virtue to success, with those who demonstrated exceptional knowledge or professional skill held in newly high esteem. Importantly, meritocracy is an individualist model of status. The status accrued by a prominent scientist does not necessarily extend to his wife or children.

This revolution was accelerated by increases in mobility, both physical and social. The Church’s imposition and enforcement of laws against consanguineous (cousin) marriage throughout the Middle Ages undermined the integrity of highly dense and isolated communities made possible by marriage between relatives.

This phenomenon is documented in the interesting study ‘The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation’, which follows the same logic:

With the origins of agriculture, cultural evolution increasingly favored intensive kinship norms related to cousin marriage, clans, and co-residence that fostered social tightness, interdependence, and in-group cooperation… Within intensive kin-based institutions, people’s psychological processes adapt to the collectivistic demands of their dense social networks. Intensive kinship norms reward greater conformity, obedience, and in-group loyalty while discouraging individualism, independence…

…we show that countries with longer historical exposure to the medieval Western Church or less intensive kinship (e.g., lower rates of cousin marriage) are more individualistic and independent, less conforming and obedient, and more inclined toward trust and cooperation with strangers.5

This is relevant because the successful accrual of status through virtue mechanisms requires one to be embedded in a largely static community with shared norms, who appreciate and reward sacrifices made for the group. Conversely, status markers associated with success (wealth, knowledge, skill) attach primarily to the individual and are fungible across groups and geographies, thereby retaining value in less dense networks.

Thus the Enlightenment initially opened up new status opportunities for men (success) whilst undermining those that supported women (virtue). We all have a psychological need for status, and so it was only a matter of time before women demanded access to and participation within success games (education, commerce, politics, even sport). Unfortunately, accruing status through success games is time intensive, and unlike virtue games, trades off directly with fertility.

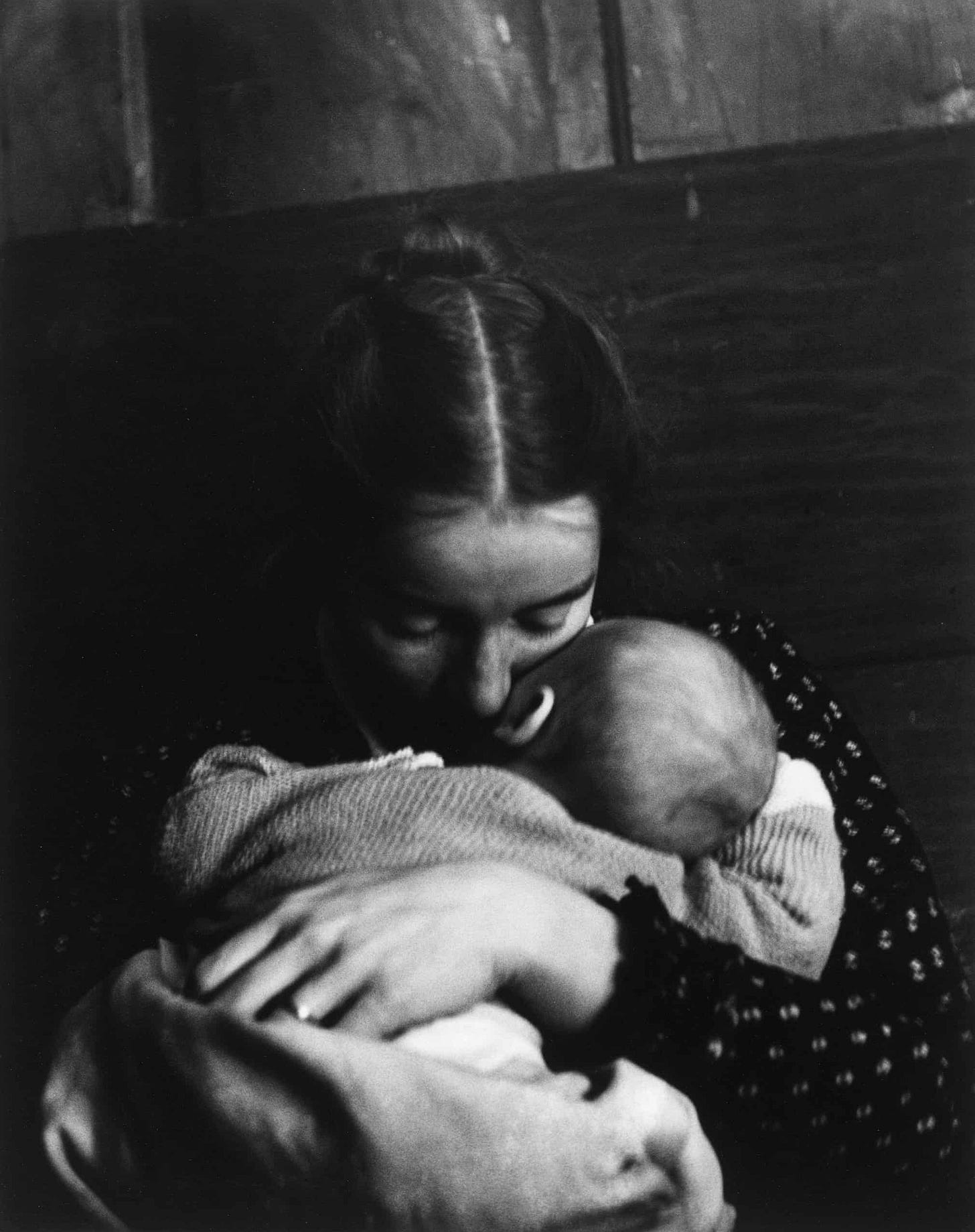

Over time, this set of status mechanics spread, intensified, and deepened, particularly during the process of urbanization during the Industrial Revolution. Ultimately this culminates in today, when the standard introductory question has become ‘What do you do?’. This is because the most effective way to gauge the status of one’s interlocutor is to understand their level of success within our meritocracy. Unfortunately, ‘I’m a mother’ is not a good answer to this question, because this conveys little status within a success framework, which is usually the operative one. Women are, understandably, hesitant to be continuously humiliated in this way, and will make whatever tradeoffs are necessary to ensure they have a better answer.

This implies that, in our quest to increase birthrates by making having children high-status again, we have two possible strategies: find a way to revive virtue games, or find a way to establish having children as a marker of success.

This takes us back to the highly fertile Orthodox Jewish and Amish groups mentioned earlier. I propose that the fundamental driver of their birthrate is not merely their religiousness, it is their isolation and in-group preference which has allowed for the preservation of virtue games. Through the cultivation of intense social density and homogeneity, they have built what I call ‘mimetic infrastructure’, which enforces people’s full participation in their religious duties if they are to maintain standing in the group.

Unfortunately the productive cultural isolation enjoyed by these minority groups makes their way of life quite alien to the rest of us, so we cannot simply ‘join in’. So what is the policy solution here?

Western governments should pursue policies which give greater space for the rise of other stable groupings of people with sub-identities, within which alternative status ecosystems can flourish. As a first step, governments must do everything they can to foster the creation of further mimetic infrastructure which supports virtue games.

These cultural colonies must be uninterrupted, to the greatest degree possible, by the state imposition of universal Enlightenment success games.

Unfortunately for liberal readers, there is no way to do this that does not conflict with Enlightenment values. However, the good news for liberals is that none of the solutions require impositions on liberals - governments just need to ease restrictions on those who wish to pursue alternatives. Most of the obvious interventions would actually save the state money, even while raising the birthrate.

The support for these communities would involve:

Not forcing their young to undergo a liberal education;

Supporting religious and home schooling;

Ending universal mandatory examinations;

Ending mandatory sex education which condemns teen pregnancy;

Allowing children to work from a young age at local businesses;

Equalizing state support for religious colleges;

Ending programs which promote universal tertiary education;

Ending universal state incentives for women’s further education;

Not forcing communities to elevate women professionally;

Not forcing communities to take migrants (domestic or foreign);

Not forcing communities to cultivate diversity;

Allowing hiring discrimination;

Allowing business discrimination;

Ending state messaging championing women’s professional success;

Ending state funding to national liberal media outlets;

Removing hate speech laws that de facto mandate particular sexual ethics;

Ending inheritance taxes that force property sales;

Removing taxes (gas, cars) that raise the cost of children.

I’m sure this list will be shocking to some, but we’re in a shocking situation. Many Western countries are committing civilizational suicide and face economic collapse within the century. Millions of people who say they want children never get to have them.

Again - none of the above make negative impositions on groups who wish to continue following a liberal agenda, although support for liberal programs will have to shift from a national to regional level. This is less radical than it may first appear. Indeed, there have been key times in our recent history - when our countries were flourishing - that all of the items on the above list were the norm.

If followed, this program would be the beginning of an evolutionary race of tight-knit communities underpinned by virtuous mimetic infrastructure. Importantly, this would convey significant benefits (even if these benefits are not the progressive set that we are used to) on their women and their middle classes.

Our task is to clear the way for the most vital of these communities to flourish - and with them, our civilization.

Thank you for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this essay, please leave a like (the heart button below) and subscribe.

Paid subscriptions are hugely appreciated, and unlock the archive of almost 100 articles on a great range of relevant subjects. All revenue goes towards supporting my family.

Wondering what to read next? Try:

Sic transit imperium,

Johann

Manning, Jason. Suicide: The social causes of self-destruction. University of Virginia Press, 2020.

Grol-Prokopczyk, Hanna. "Celebrity culture and demographic change: The case of celebrity nonmarital fertility, 1974–2014." Demographic Research 39 (2018): 251-284.

Balbo, Nicoletta, and Nicola Barban. "Does fertility behavior spread among friends?." American Sociological Review 79.3 (2014): 412-431.

Storr, Will. The Status Game: On Human Life and How to Play It. William Collins, 2021.

Schulz, Jonathan F., et al. "The Church, intensive kinship, and global psychological variation." Science 366.6466 (2019).

I’m a stay at home mom who was born in the downtown area of a liberal city… it feels like punk rock rebellion these days to be a sahm, especially a sahm who isn’t trying to start some coaching side hustle.

We can all do our bit in raising the status of SAHM - next time you see a mum out and about with her kids, simply tell her what a valuable job she is doing. Someone took the time to say this to me as I was herding our 3 kids into the bakery queue last week and it lifted me up for the whole day. Such a refreshing change from the 'woah, you've got your hands full' and 'are they all yours' comments people usually make on our outings.